Phytoremediating Villa Galilea

Valdivia, Región de Los Ríos, Chile

by Paloma Lenz

Flourishing amid Valdivia's river-sculpted landscapes, mycelium finds its thriving niche

within the humid and rainy Los Ríos region.

Operating akin to fungi’s vegetative component, the Corporación Humedales de Angachilla (CHA) protects a nature sanctuary as a decentralized entity comprising a network of 30 smaller local organizations.

Most committees represent one of many poblaciones, or planned communities, in Valdivia, Chile, as well as groups devoted to carrying out a spectrum of roles. These roles include environmental advocacy, community outreach, forest fire control, water quality monitoring, and water body conservation.

Along the Edge &

Cutting Through

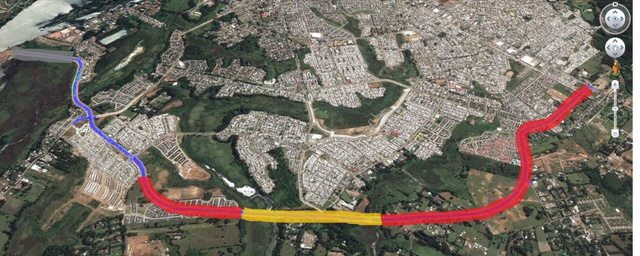

Even before the CHA was created, Valdivians and community organizations living alongside the wetlands spoke out against wetland-threatening construction. Around 2013, the CHA began to vocalize evidence-based pushback against plans for urban expansion into the wetlands that border Valdivia. One such project, which aims to construct a circunvalación, or circular bypass, for transportation throughout Valdivia, proposes to bridge the communities that border wetlands. The first stage of this project has already minimized traffic congestion, but at the expense of thinning wetlands. To criticize this project, the CHA has synthesized research on the Angachilla wetlands’ water quality, geological history, indigenous significance, and cultural vibrance. Archaeological finds have slowed the project considerably, which legally require thorough investigation and designation as a patrimony site. Fortunately, local organizations have established a dialogue with authorities to evaluate alternative road layouts. Still, the challenge lies in satisfying all parties and prioritizing environmental conservation.

Media Credits: Sergio Esteban & Skyscraper City

El Santuario de la Naturaleza

Still, the wetlands’ valor as a critical natural habitat and filtration site has only recently been recognized with its designation as the Santuario de la Naturaleza, an officially protected natural space. As the Santuario’s administrator, the CHA can exercise relatively strong monitoring and policies within this domain. In a recent victory, the Municipality of Valdivia successfully secured a legal triumph against an individual who had unlawfully filled sections of the Angachilla wetland from 2018 to 2019, driven by commercial interests.

However, this designation does not sufficiently extend to areas in critical condition. Even with these forms of political support, citizen behavior and limited environmental education also exacerbate the challenges that come with wetland conservation.

Motivated by emerging municipal funding opportunities and their unbridled passion, the CHA aims to embark on a new program focusing on community water monitoring, surveillance, trail maintenance, and pollution reduction. I was beyond excited to offer my ideas for the design and implementation of a simple, low-cost phytoremediation system in Villa Galilea: hopefully, the first site of future pilot projects.

Villa Galilea

Villa Galilea is a community located on Avenida Circunvalación Nueva Región in Valdivia. Claudia and Sergio, Galilea inhabitants, members of the CHA, and leaders of their own projects and organizations Ecobarrios, CletaCompostera, and the Comité Ecológico Bosque Humedal del Santuario Angachilla introduced me to several rainwater discharge points.

The Comité Ecológico has already constructed signs identifying native species, installed trash cans, cleaned up litter, and grown plants for enjoyment by the community’s inhabitants. During my first site visit, I followed Claudia and Sergio along the trail they outlined using branches and rocks toward the Angachilla wetland. Descending along the trail, we were met by the sight of makeshift wooden headstones, rainbow pinwheels, and fake flower bouquets, evidence of pet burial sites. Unfortunately, poor burial methods increase the risk of resurfacing and potential leeching of decomposition gases (methane and hydrogen sulfide) into the soil. There isn’t an inch of the city that doesn’t see a perro callejero, or street dog, due to high rates of pet abandonment. These burial sites, and many of the native birds that inhabit the wetland, are sometimes disturbed by these animals.

We walked closer to the stormwater discharge point, where we received playful requests for a fresh pair of socks from a group of boys, all wearing soaked shoes. As they scurried away, we found cow tracks in their place. Claudia explained that cattle and horses regularly traverse the stream here in the middle of the city, led to fresh helechos (ferns) by a local farmer.

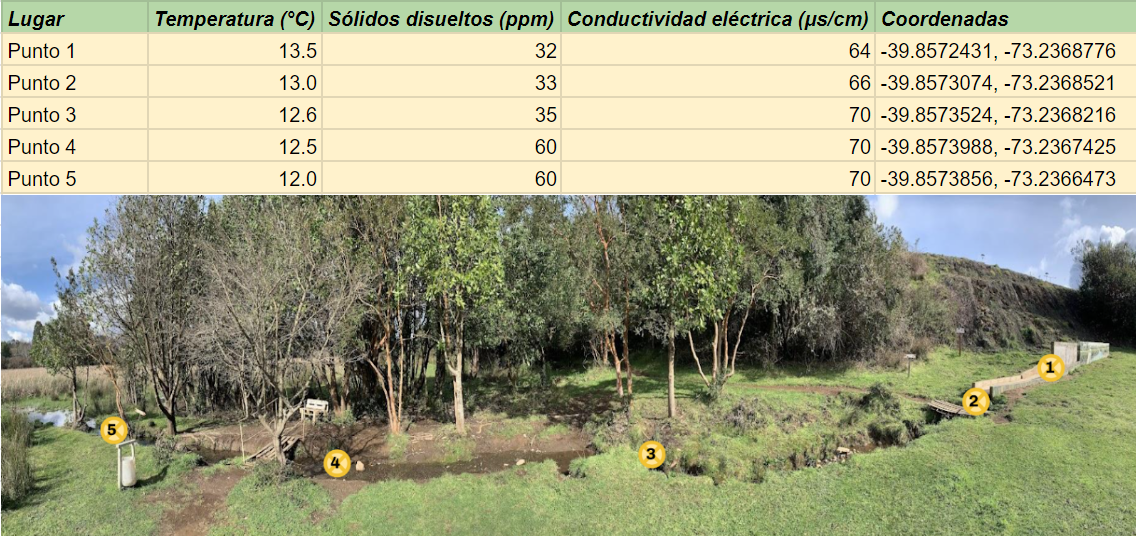

As is the case on the sidewalks and streets of virtually all cities, concrete’s purpose is never to absorb material. Here, water is immediately channeled away from Villa Galilea’s streets. With heavy rainfall, too, the water slices the earth and rapidly erodes ground that isn’t stabilized by deep plant roots. Our water quality analysis (which analyzed temperature, dissolved solids, and electrical conductivity) indicated the following results:

Temperature (°C)

Dissolved solids (ppm)

Electrical conductivity (µs/cm)

Coordinates

Location

The results indicate that the water's quality was less of a concern than the structure of the stream itself. Given that some of the main threats to the wetland entrance were the amalgamation of garbage and eroding streambanks, we decided to design a simple, yet effective, phytoremediation system.

Reclaiming with Nature

We capitalized on plants' ability to absorb trace contaminants from water and the natural purifying capacities of layers of sand, rock, and earth. Plant stromata and roots absorb air- and water-born pollutants for digestion. The roots of plants themselves also physically stabilize riparian buffers, protecting riverbanks from erosion.

We made use of several native species: Chusquea quila, Pteridium aquilinum, Schoenoplectus californicus, Lemna valdiviana, Drimys winteri, and Cyperus eragrostis (otherwise known locally as quila, helecho, totora, lenteja de agua, canelo, and cortadera grande, respectively). Quila was used as a fence to protect transplanted plants from cattle and to construct simple trash barriers. Small rock fences were also stretched across the stream to stabilize the quila and streambed.

Our design is sensible, humble, and biomimetic: it uses natural resources found within one mile of the project site, accounts for shifts in water flow, repurposes materials, and values the contributions of every participant. The solution is not energy-intensive, nor does it pose a financial barrier; this ensures the reproducibility of the project in other wetland-bordering communities that don’t have access to resources for expensive designs.

After two site visits, two material collections, and two group construction events–which gathered over twelve local community members during a torrential downpour–the system was successfully constructed. The CHA will closely monitor the water quality to test the effectiveness of the system. We celebrated our success (over sopaipillas and pebre!) and vowed to sustain this energy for future projects.

I extend eternal gratitude to the CHA for placing their trust in me. I eagerly await my next visit to Valdivia to witness their mission's expansion!